Algae just might have superpowers. Packed with nutrients, including high levels of protein, essential amino acids, vitamins and minerals, some species are considered a ‘complete’ food. Algae can confer immune support and have anti-inflammatory properties, reducing the likelihood of cancer and heart disease, among many other benefits to human health.

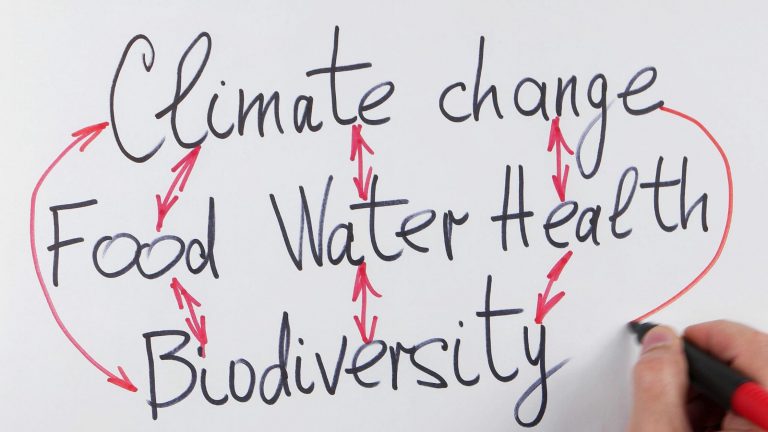

But that’s not all. Algae can be used as animal feed or additive, fertiliser and fuel. There are few downsides to its production. Algae use far fewer inputs than terrestrial agriculture such as freshwater, fertiliser and land. They can cycle out pollutants in the environment rather than adding them. And they contribute to carbon capture and storage to help mitigate the effects of climate change.

Is there anything algae can’t do?

This series of articles explores the potential for this amazing and underappreciated group of organisms to help transform our food systems, starting with our health.

Let’s start with the basics: algae are not plants

Algae are regularly described as ‘sea vegetables’. This is clever marketing when used on food packaging and makes it easier for us to associate these unfamiliar life forms with something recognisable in Western diets. Although plant-like, algae lack the complex structures of terrestrial photosynthetic organisms. They are generally (but not always) categorised as protists, a taxonomic grouping for organisms that are not plants, animals, or fungi: members of a different living kingdom altogether.

Phycologists are the scientists who study algae. But even those who are closest to these incredible organisms don’t know how many species there are worldwide. The estimated range is between 30,000 and 1 million. Many species are thought to be undiscovered. And there are debates about how to classify them.

More than 30 species are regularly produced or harvested commercially, only 6 of which represent most of the algae intended for human consumption. This can be direct—like the seaweed sheets used to make sushi—or indirect, as a food additive with beneficial characteristics that are functional (conferring health benefits beyond basic nutrition), preservative (for their antimicrobial properties), or structural (as an emulsifier, thickener or gelling agent).

Algae come in two sizes: macro and micro

When we think about algae as a food source, it’s probably seaweed that comes to mind. Sushi fans might immediately think of nori – the paper-thin wrappers that bind together rice, fish and other ingredients into a perfect, edible package. Or maybe wakame, the star of the show in that bright green, slightly gelatinous seaweed salad. You may have even noticed seaweed snacks, made from laver or kelp, tucked between the tortilla chips and potato crisps during a recent trip to your local supermarket.

Seaweed is macroalgae: visible with our naked eye. It comes in shades of green, brown and red. But there are edible microalgae, too, such as Chlorella. And cyanobacteria that are regularly classified with algae, of which Spirulina is probably the most well-known. I remember going into a café in Los Angeles 20 years ago and seeing Spirulina on the menu as something you could add to your fruit smoothie. I gave it a miss back then. I’m rethinking that now.

Humankind evolved in close partnership with an algae-based diet

Archaeological evidence indicates that algae were an important food for thousands of years in parts of Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. The fully modern brains of our species, Homo sapiens, may even have developed at least in part due to access to coastal waters, rich in edible algae.

Brain growth requires sufficient levels of iodine – a trace element in short supply on land, but abundant in the ocean. It also requires DHA – one of the omega-3 oils also found in fish and other marine animals (due to their direct or indirect consumption of algae). Deficiencies of either iodine or DHA can restrict cognitive development in foetuses and children. In sufficient quantities they have enabled human flourishing.

This seems a fortuitous start to the human-algae relationship.

The importance of algae to Western diets has ebbed and flowed

Seaweed is perhaps most familiar in Western diets these days for its importance in Japanese, Korean and other Asian cuisines. My abiding connection to algae certainly comes from the first time I ate sushi when I was an undergraduate in New York City.

Health buffs may think of Spirulina or Chlorella supplements for their smoothies. These microalgae contain high levels of many important nutrients, which has resulted in a kind of cult following amongst the health conscious. Algae are now regularly referred to as ‘superfoods’.

Some species have long been consumed as traditional foods. In Ireland and Scotland, dulse is used to make soda bread and as an ingredient in soups and stews.

In Wales, laver is sometimes referred to as the Welshman’s caviar and used to make laverbread. Not to be confused with anything made from flour and water, laverbread is seaweed pulp, minced or pureed to form a paste. It’s traditionally eaten on its own, mixed with oats and fried into a patty or spread on toast.

Dulse and laver declined in importance as a foodstuff over time. But they have recently been making a comeback, mostly as an artisan food product.

Commercial scale cultivation is increasing in the UK (although still a tiny part of the global market) and across the EU, with top producers including Spain, France and Ireland. And, of course, the US is developing its own algae markets, too. The 2018 Algae Agriculture Act even put algae on the same footing as more traditional crops for the first time. That’s because consumers are beginning to consider algae, not as a speciality food for foragers, health fanatics or Asian food fans, but as a regular part of the diet, due to their high nutritional value and sustainability benefits.

In contrast, algae are a mainstay of many Asian diets

Algae consumption in Europe and North America pales into insignificance compared to its role in Asian diets. In East Asia, algae have played an important culinary role for centuries, valued for their nutritional properties and as a flavour enhancer. The Japanese eat about as much seaweed as Europeans do salad; the Chinese and South Koreans consume even more.

This region produces most of the world’s algae as well. China, Indonesia, Korea and the Philippines are by far the leading growers and gatherers of edible algae. More than 97% of world algae production occurs in Asia.

Are algae true ‘superfoods’?

Algae are generally a highly nutritious food source: low-fat, fibre-rich and nutrient-packed.

They contain an abundance of important micronutrients, including iodine and DHA, which I’ve already mentioned are essential for cognitive development. Algae have high levels of many vitamins and essential minerals. These include A, D, E, K, C and B-vitamins, as well as calcium, iron, iodine, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium and zinc.

Some species (microalgae in particular) are protein-dense, with the full complement of essential amino acids that the body needs – similar to animal proteins and in contrast to most plants.

Unsurprisingly, then, algae have many health benefits. These include improved gut health, and immune support. Ample published research demonstrates that algae can reduce the risks of the main non-communicable diseases: cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. Together with chronic respiratory diseases these conditions are responsible for almost 75% of all deaths globally each year.

Nevertheless, there are many variables to consider. Nutritional composition varies widely by species. Nutrient levels can vary even for the same species depending on the environment in which it grows. The manufacturing process can also affect nutritional content, of course (as it can of almost any food). And critically, there remains much that is unknown about the bioavailability of all those nutrients, how the nutrients interact in the gut microbiome, and how much one would have to eat to get the full benefit of any of those nutrients.

And there is one mineral that algae have an abundance of that clearly can be harmful in high doses: sodium. So it’s important not to overdo it!

Still, the health benefits by far outweigh the risks when algae are consumed as part of a well-rounded diet.

Why aren’t we eating more of these sea vegetables?

Algae impart salty and umami flavours to foods, intensifying their savouriness and depth, making them tasty as well as healthy. They provide the opportunity to be a sustainable food source, as well.

With so much to offer, it’s a shame that we aren’t eating more of it. My next article discusses the environmental and other benefits of algae, and the opportunities and challenges of giving it a more prominent role in our diets.

I write about the future of food and the connections between our food systems, the environment and public health. Sign up for my newsletter.

You can also read more here.